One is never wrong if they call Citizen Kane the greatest American film of all time.

Unfortunately,

this safety net has in fact come to work against the film in recent years. Many

people coming to the film for the first time are so overburdened with

expectations concerning the picture’s sizeable reputation that their first

viewing inevitably leaves them both disappointed and rather curious what all

the fuss was about to begin with. Others resist labeling Citizen Kane ‘the greatest’ for other, more obvious motivations:

They want to be different and buck the convention wisdom.

Neither

condition applies to me.

I

first encountered Citizen Kane in a

high school film class and I found its perspective, wherein a newspaper

reporter interviews several characters about Kane and the narrative of the

picture leaps between time periods in an almost disjointed fashion, completely

enthralling. For me, the richness of the film’s themes, its technical

achievements and its overall artistic vision have not dulled with time, either.

This is quite simply the greatest American film ever made, no matter what

criteria one is asked to consider, and it will remain such, I believe for

eternity.

Indeed,

there are so many angles one can come at when discussing Citizen Kane—a testament, I believe, to its greatness—that one

almost does not know where to begin. There are its many technical achievements,

in which set design, costuming and makeup reached hitherto unforeseen heights

in film. There is the cinematography. Never before had light and shadow been

used so effectively, actors positioned in such crucial ways and cameras positioned

in such strange and wonderful places (Orson Welles famously cut the floor out

of some sets to shoot up and at his actors from their feet to make them appear

larger than life).

However,

the construction of the film’s narrative and the underlying themes that

narrative contains are where I believe Citizen

Kane is at its greatest.

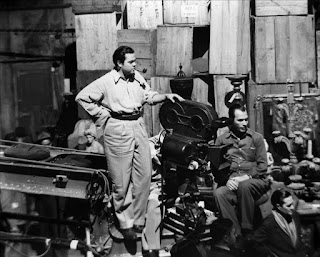

Orson

Welles, a man who needs no real introduction to contemporary readers, for

better and worse—mostly worse, if you know anything about Welles—was at the

height of his powers when he made Citizen

Kane and the choices he makes as a storyteller are inspired. I have no

evidence Wells read William Faulkner or James Joyce, but the notion the

conventional narrative underwent a serious revision in the 1930s and 40s should

be apparent to even the most casual reader of American and world literature

from that time period. Furthermore,

Welles in his infamous “War of the Worlds” broadcast had already demonstrated

during the 1930s that he had a penchant for turning the conventional narrative

on its head through the innovative use of established mediums.

His

application of this in Citizen Kane

is clear in that he takes the traditional film noir narrative of a mystery in

need of solving (in this case about Kane’s last words), fatalism and trust and

betrayal and enlarges the genre to tackle nothing less than the entirety of the

American dream and what it means to gain and lose things (people, power, love,

adoration, hate and prestige). In a film so about narrative, it is telling we

never hear from Kane himself. Rather, he is a corpse from the very first frame

of the film and instead we hear from those who knew him at his best and his

worst, as the narrative leaps here and there and provides sharp and soft shards

of a man’s life, who by his own account could have been a great man, but was

not.

And

yet, for all the cinematic bells and whistles (and what a movie this is JUST to

watch, even on mute), for all its tricks of camera and flashes of brilliance,

this is at its heart a film about people and their failure to interact with

another, to love one another and to live to meaningful lives. All of the

characters in Citizen Kane are

haunted ghosts, empty reflections of a former “greatness” that when peeled away

turns out to be far more prosaic and ordinary than we first believed. Kane’s

longtime sidekick still remembers a nameless woman he never spoke to but

glimpsed on a New York pier, Kane’s best friend just wanted to write an honest

review of Kane’s wife because he could not remember how to do anything honest.

These

are small, simple acts (or non-acts) and yet they all had more impact than Kane’s

failed gubernatorial bid or the Second World War on all of those involved. That

is because in the end, Citizen Kane

is about the roads not taken or the decisions made or not made and what each of

those moment renders in the years that follow. What is a life but the fragments

of where it touched other people? Kane’s physic interior can be guessed at, but

never known. What can be known, both by him and all the other characters, is the

decisions they all made and how those decisions created their lives and

formed them into the people they became. Thus, Kane’s “Rosebud” was a sleigh

ride never taken, a life of complete ordinariness in Colorado wilds that was

never possible after his mother sent him East with his millions.

That

he seemed willing to trade all the subsequent moments, all the subsequent

decisions and outcomes for a chance at that lost life is the tragic nostalgia at the heart

of Citizen Kane’s power as a film.

For who among us believes every path

we chose was the correct one? That all of those roads not taken were

truly unworthy of exploration?